Abortion Access in Eastern Kentucky

As of 2020, there were 65 million women of reproductive age living in the United States. More than 19 million women with lower incomes live in contraceptive deserts, where they lack reasonable access to a health center that offers the full range of birth control methods. Moreover, nearly 2.2 million women live in maternity care deserts, lacking access to a hospital that offers obstetric care, a birth center, and an obstetric provider. Such inequities in access to timely, affordable, and essential reproductive health care services are magnified in rural America, driven by factors such as high rates of poverty, geographic isolation, lack of transportation, a shortage of health care workers, misinformation, and stigma. As a result, rural residents commonly experience poorer reproductive health outcomes compared to their urban counterparts. And with the Supreme Court’s recent overturning of Roe v. Wade and an increase in dangerous abortion bans, rural communities will face even greater challenges in achieving reproductive well-being.

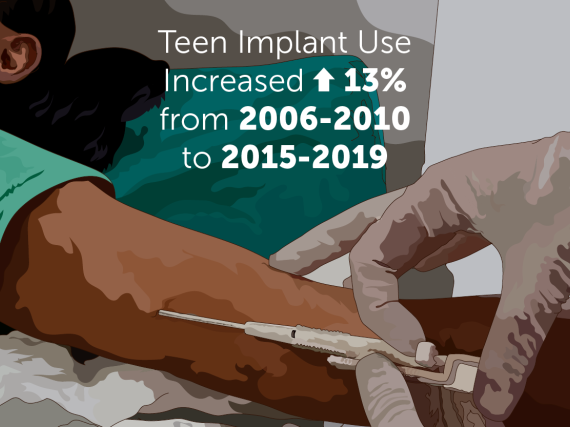

Kentucky currently has some of the most restrictive abortion policies in the US, including a near-total abortion ban. As a public health practitioner and native of an Appalachian Kentucky community, I deeply understand how this abortion ban will disproportionately impact rural residents, families, and communities. Nearly half (49%) of people in Kentucky live in rural areas, making them more likely to be on Medicaid. Statewide, 47% of all pregnancies are described as unplanned by pregnant people themselves, and approximately 270,000 women live in a contraceptive desert. Prior to the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Kentucky had only two abortion clinics, both of which were in our state’s largest city, Louisville. For eastern Kentucky residents, this could mean a journey of more than eight hours to access care, requiring a patient to obtain transportation and lodging, take time off from work or school, pay for childcare, and secure sufficient funds for the procedure itself. On average, the median out-of-pocket cost for an abortion exceeds $500. With a rural poverty rate of 19.2%, abortion care may be out of reach for many rural residents. Limited access to abortion care can result in long-lasting economic, social, and health consequences. For example, research shows that women living in poverty who are denied abortion care are more likely to remain in poverty than those who are able to obtain abortion care.

Currently, the only exception to Kentucky’s abortion ban is lifesaving measures, but who should get to decide what is lifesaving for an individual? Looking through a holistic lens, “lifesaving” should have myriad meanings. Certainly, medical complications such as an ectopic pregnancy or severe infection should prompt access to a lifesaving abortion. For others, “lifesaving” is the opportunity to pursue an education, establish a career, overcome poverty, and establish a safe and stable living environment.

For far too many, equitable access to abortion care is seemingly reserved for the privileged—a phenomenon that is all too familiar for impoverished and minority individuals. I firmly believe that everyone, regardless of their financial circumstances or geographic location, should have the right to decide if, when, and under what circumstance to get pregnant and have a child. While abortion bans and restrictions threaten this fundamental right for millions across the nation, we cannot overlook the disproportionate harm inflicted upon marginalized populations, like our rural communities. As reproductive health advocates and as a society, we must implement policies that are backed by science, prioritize equity, and ensure that full spectrum reproductive health care is not just a luxury for some, but a constitutional right for all.

Kelsie Williams is the Project Director of All Access EKY, where she leads efforts to support access to the full range of contraceptive methods and quality reproductive health services. As a native of eastern Kentucky, Kelsie is passionate about increasing opportunities and empowering people to make decisions about their reproductive well-being and their future, with a particular interest in creating equity in rural, underserved communities. Kelsie is an MPH Graduate of George Washington University-Milken Institute School of Public Health.